VIRTUAL EXHIBITION

Join us on a journey of discovery, explore the musical heritage and experience the interconnected cultural roots of Europe.

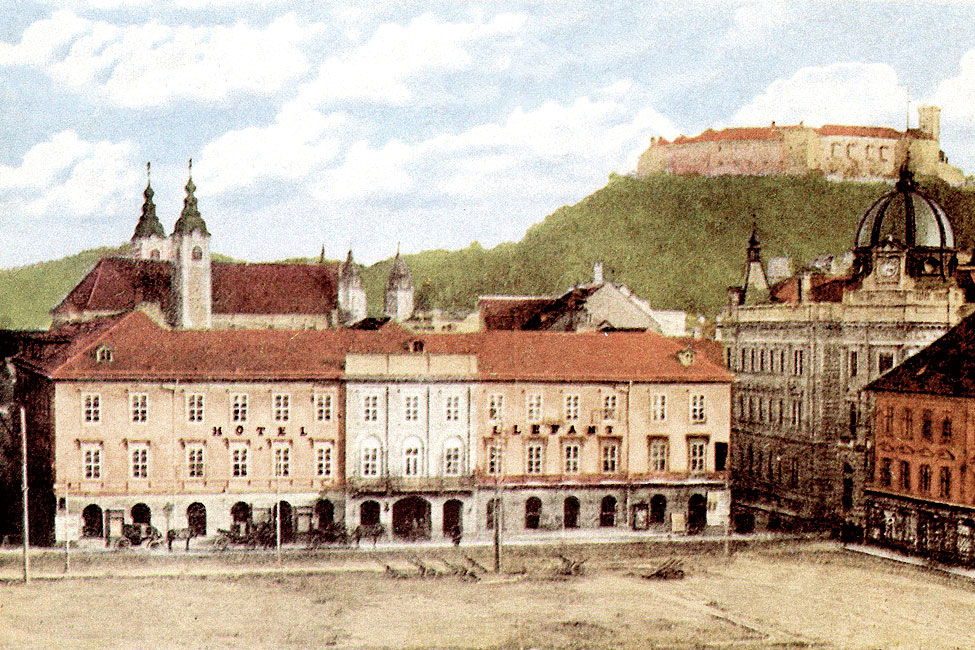

The day before his journey from Graz to Ljubljana, the son of a famous composer, Franz Xsaver Mozart, wrote in his diary: “Tomorrow I am going to boring Ljubljana and only now I am aware of how much I enjoyed Graz”. But fortunately, an aspiring Bohemian musician, Caspar Maschek, did not find Ljubljana boring and moved from Graz to the city that same year, where he soon became one of the most important musical figures in the capital of Carniola. He was soon followed by a number of other talented musicians who began their musical journey in this city, located at the crossroads between culturally dominant Vienna and cosmopolitan Trieste on the Mediterranean coast.

Immigrant Musicians

II. MUSICAL LIFE OF LJUBLJANA

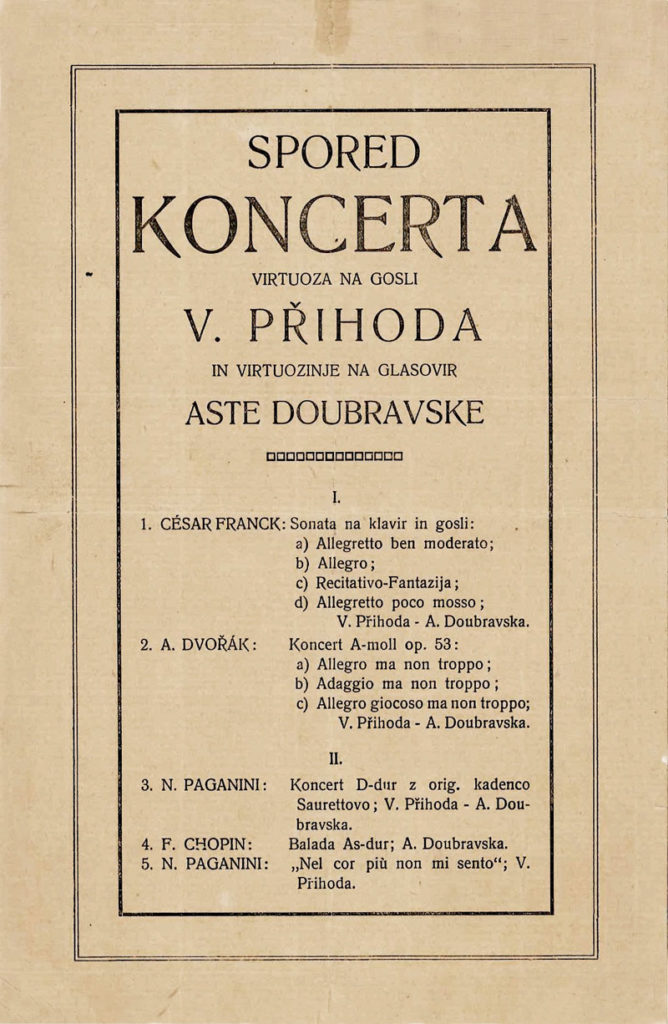

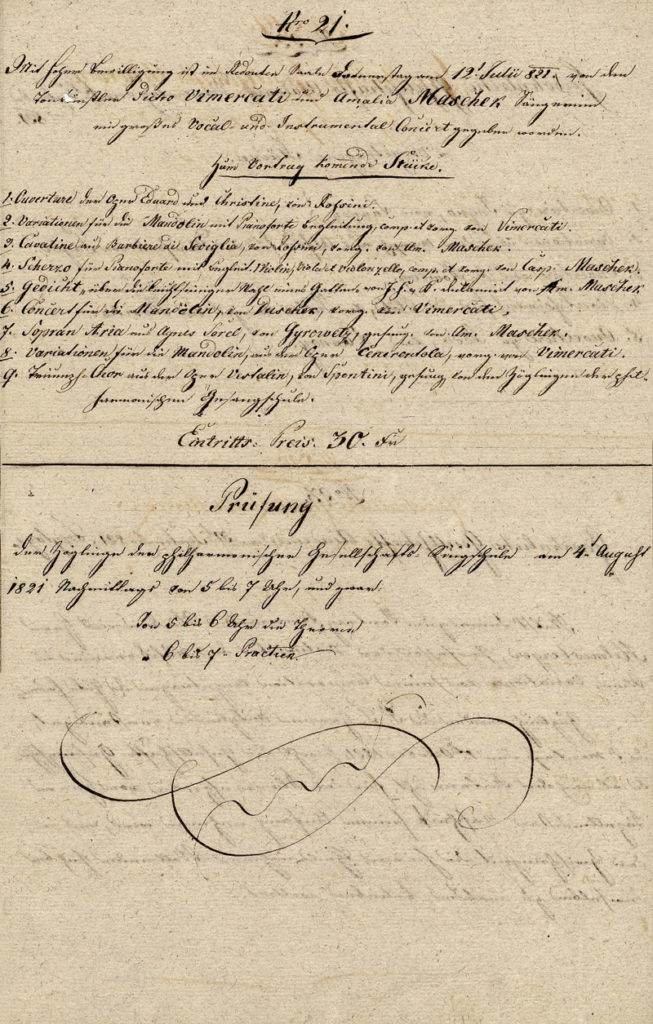

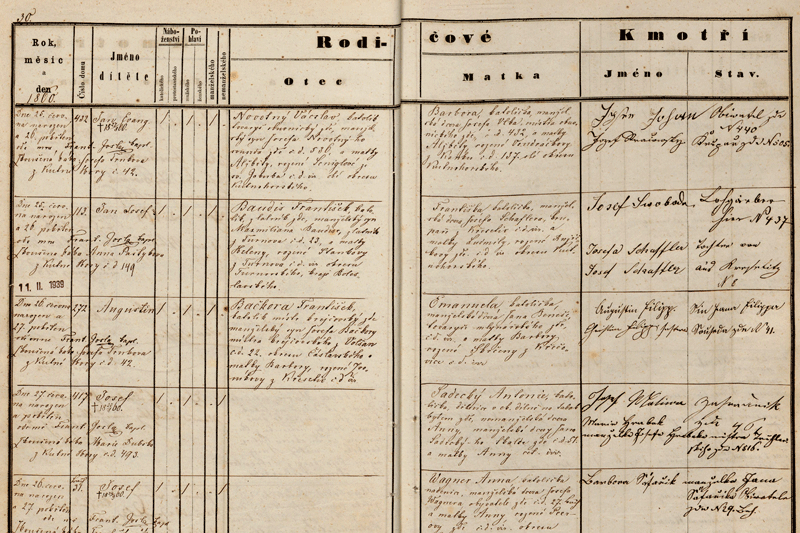

The Habsburg Monarchy was a vibrant multiethnic state with substantial regional mobility, in which Ljubljana was an important and well-connected crossroads between Vienna and Trieste. Travel was handled by a regular postal service and, from the late 1840s onwards, by the Austrian Southern Railway. For this reason, the paths of many travelers, including artists, virtuosos, music traders, and music supporters from the emerging bourgeoisie and aristocratic circles crossed paths in the capital of Carniola. Musical trends such as performance styles and compositional practices reached the city in various forms and through various channels. Foreign musicians (mainly migrants) played a major role in this phenomenon, participating in concerts held by the Philharmonic Society, founded in 1794. Some of them settled in Ljubljana temporarily or even permanently, whereas others responded to personal invitations or to a vacant teaching post. They made key contributions to the musical activities of the Philharmonic Society, the Ljubljana Cathedral Music Chapel, the Estates Theatre, and the military bands, as music teachers in the context of various music societies or in a purely private capacity. From the second half of the nineteenth century, immigrant musicians became increasingly involved in Slovenian music institutions. In the early 1860s, the Ljubljana Reading Society (Čitalnica) became the center of Slovenian cultural life, regularly hosting recitals (bésede). A decade later (1872), the Slovenian-language Music Society (Glasbena matica) was founded, and it became the central music institution of the city. According to recent counts, these institutions gave over 1,550 concerts in Ljubljana between 1816 and 1919. The majority of performers at these concerts were guest musicians and migrants. They were of particular importance for the city’s musical life, because they brought in the latest trends in performance and repertoire: at first, they popularized the latest opera hits (fantasies, variations, and potpourri on opera melodies), and in the second half of the nineteenth century they introduced new repertoire and contributed to the development of music in Slovenia as composers and performers.

Prelude

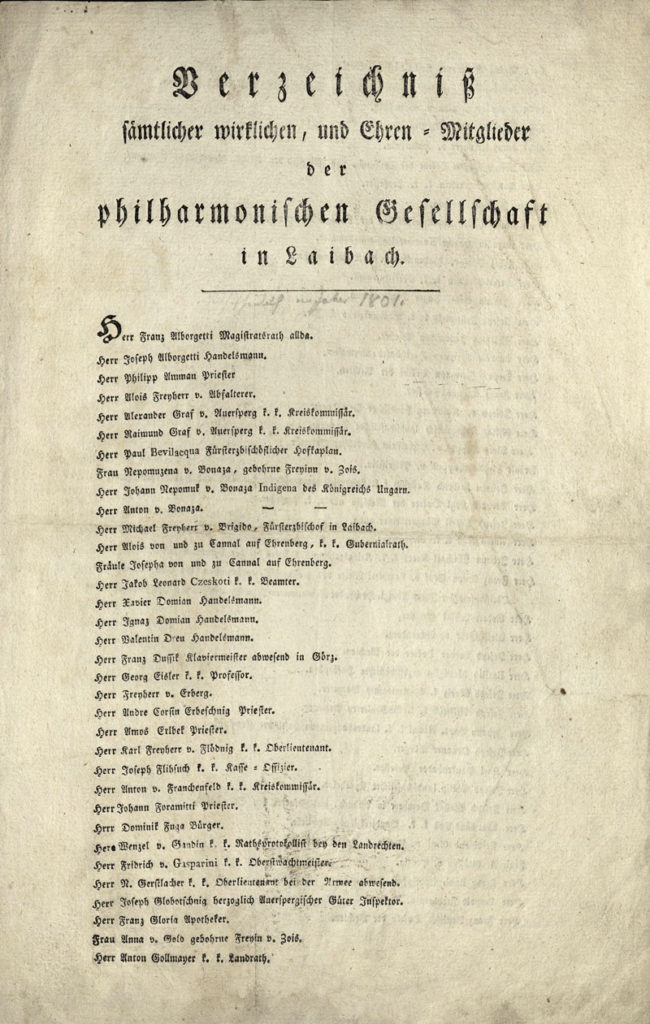

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

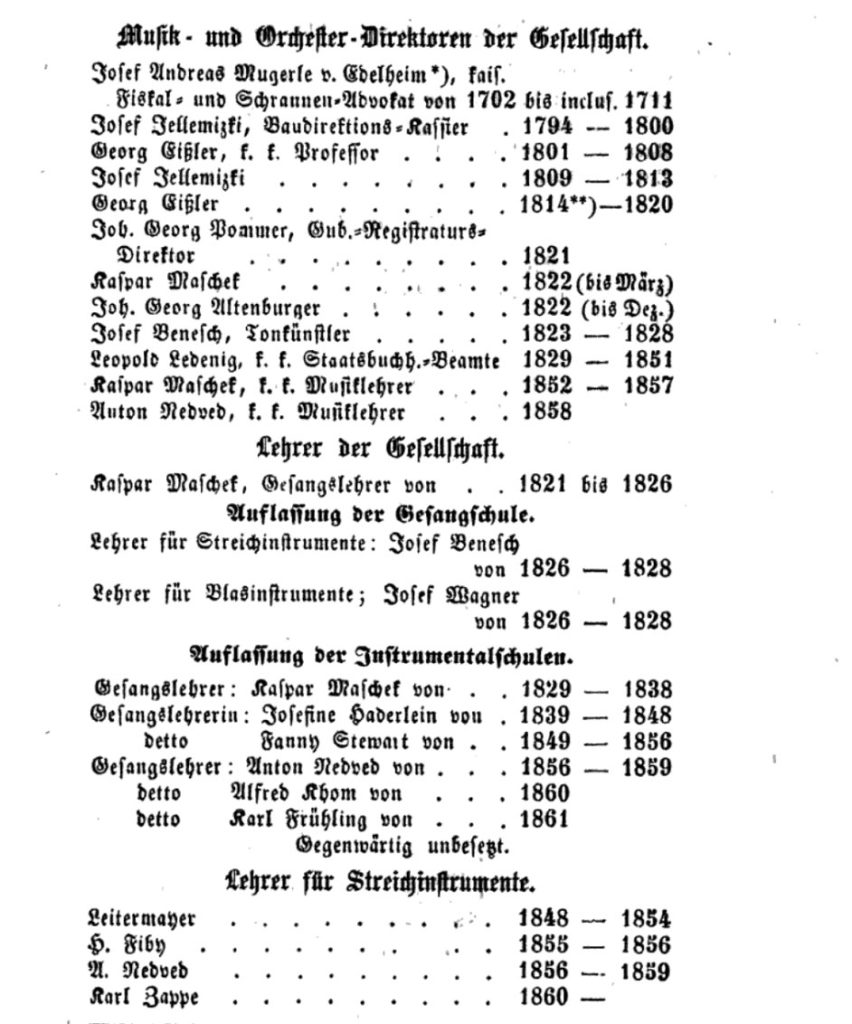

The Philharmonic Society was the first institution of its kind in the Habsburg Monarchy, founded in 1794. The society initially consisted of a string quartet of four enthusiasts. A few months later, other music lovers joined the society. The aim of the society was “to ennoble the emotions by the selection of good compositions and to form the taste by good performances within the circle of the society.” Until 1836, these events were called academies, and they were initially limited to a closed circle of society members. As for women, the statutes stipulated that only musicians who contributed to the society’s goals could become members. The Philharmonic Society also invited foreign “friends of music” to become honorary members. Several important musicians were made honorary members of the society, such as Josef Haydn (1800), Eduard de Lannoy (1817), Joseph Böhm (1818), Karol Lipiński (1818), Johann Peter Pixis (1818), Ludwig van Beethoven (1819), Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart (1820), Georg Hellmesberger (1821), Niccolò Paganini (1824), Leopold Jansa (1841), Johannes Brahms (1885), and Joseph Hellmesberger (1891). Until 1919, the society gave numerous concerts, contributed to various other musical events, and from the 1820s also strongly promoted music education, thus ensuring a lively musical life in the city. Musicians from abroad played a main role in the society, acting as its music directors, choirmasters, orchestra directors, teachers, performers, and composers. The most important of these were Gašpar Mašek, Joseph Benesch, Anton Nedved, Josef Zöhrer, and Hans Gerstner.

Establishment

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

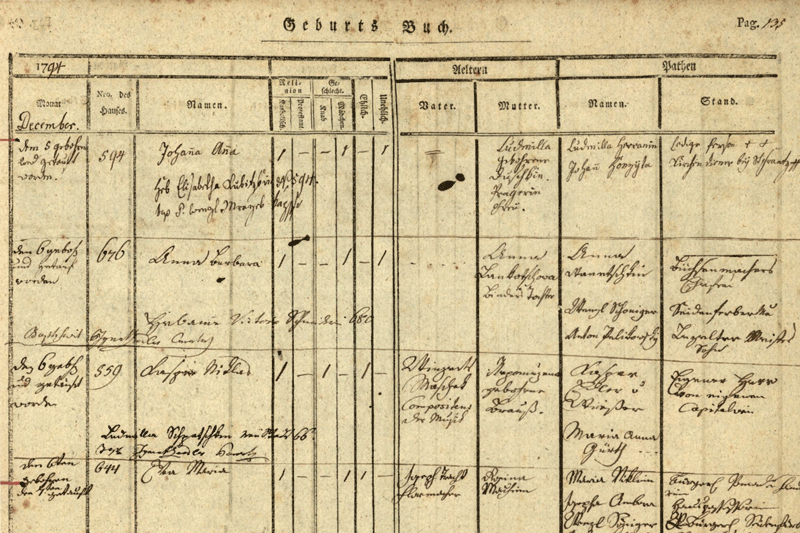

Ljubljana’s Philharmonic Society (Philharmonische Gesellschaft) was founded in the autumn of 1794 by four music lovers: Karl Moos, Karl Bernhard Kogl, Joseph Flikschuh, and Joseph Jellemizky. They founded a string quartet and performed compositions by Ignaz Josef Pleyel, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and several other contemporaries. The core of the society initially consisted of fifteen members and four quartet members. The first academy was held on 12 November 1794. The program consisted of a string quartet and a “short symphony.” Later the concert programs consisted of a predetermined sequence of musical genres, and the soloists featured in each concert appeared only two or three times during the concert. The first version of the Ljubljana Philharmonic Society Statutes (Statuten der musikalischen Geschelschaft zu Laibach) was printed in 1796. The statutes were subsequently amended, revised, and supplemented several times.

Honorary Membership

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

An important mechanism by which the society established valuable connections with eminent musicians and music lovers from 1794 onward was the honorary membership system, which served primarily to enhance the society’s prestige and attract prominent representatives. Most of the notables of Ljubljana were regular members of the society, whereas those with special merits were made honorary members. Any member who had to leave the society for professional reasons received the honorary title automatically, and the title was also given to foreign “friends of music” who could benefit the society by their “outstanding talents and merits.” Later, the rules for new admissions became stricter, and candidates for honorary membership were required to send their compositions and news and reports about their work to the society. Honorary members contributed to the society’s musical life in a variety of ways: as guest musicians, donors and dedicatees of compositions, with reports on their musical work and other news, or as advocates for the society. Several foreign musicians who lived in Ljubljana received honorary membership.

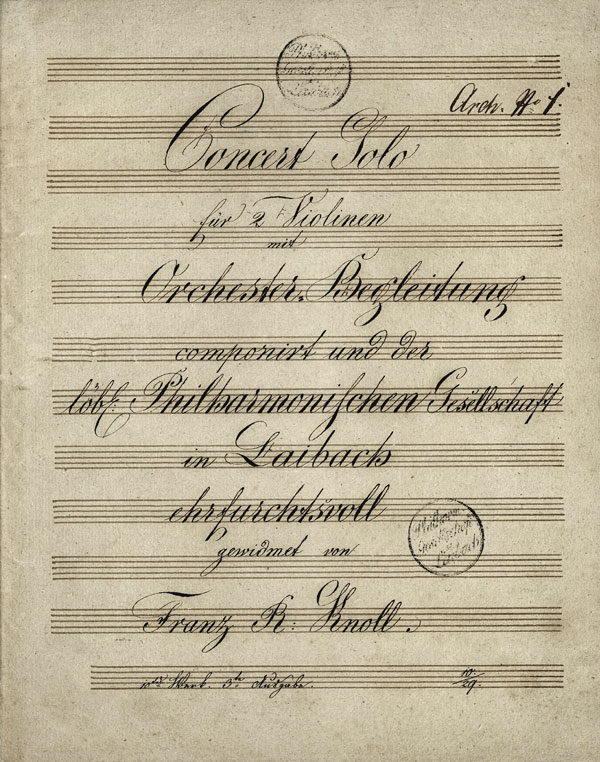

Music dedications

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

Foreign composers often dedicated their works to the society but immigrants were rarely among them, because they usually contributed to the society in other ways. Franz Knoll (ca. 1804–?) dedicated his Concert Solo für 2 Violinen mit Orchester Begleitung to the society. He came from Vienna and worked in Ljubljana between 1830 and 1831 as orchestra director of the Estates Theater and as a private teacher.

Immigrant musicians often also dedicated their works to the children or wives of important Ljubljana noblemen and bourgeoisie, usually also members and supporters of the Philharmonic Society. Joseph Benesch, for example, dedicated his work, Polonoise pour le violon avec accompagnement de deux Violons, Alto et Violoncelle op. 7, to Johann Victor von Schmidburg (1815–1859), the son of Baron Joseph Camillo von Schmidburg (1779–1846), the governor and president of the provincial estates of Carniola and patron of Ljubljana’s musical life.

Immigrant Musicians’ Contributions

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

One of the society’s founders was an amateur musician from Bohemia (“Bohemus Weissaug”) named Joseph Jellemizky. He was also the first orchestra director of the society until 1800. The foreign influx continued apace, and for more than a century musicians from abroad played a key role in the Philharmonic Society’s work and constituted the majority of its musicians. By 1919, more than forty musicians from abroad were employed by the society as orchestra directors (concertmasters), music directors (conductors), choirmasters, and teachers. These musical migrants, who in some cases were also employed by other music institutions, participated in more than 1,200 major concerts of the society as soloists, conductors, choirmasters, and composers.

Musicians’ Origins

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

Most of the Philharmonic Society musicians, both employees and performers, came from within the borders of the Austrian Empire, mainly from Vienna and smaller towns in Bohemia. A smaller group of musicians were born beyond the borders of the Austrian Empire, including in cities as far away as London, Jelgava (Latvia), and Odesa. Regardless of their origin and place of birth, they came to Ljubljana mainly from the musical centers of Vienna, Prague, Linz, and Graz, and to a lesser extent from other cities. The Philharmonic Society mainly attracted young and unknown musicians who were at the beginning of their careers and had been trained in Vienna and Prague, but also in Graz and Leipzig, and more rarely in other cities.

Origins of musicians employed by the Philharmonic Society

Concert Life

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

The Philharmonic Society was the most active concert institution in Slovenia during the nineteenth century. The oldest preserved concert programs date back to 1816. Immigrant musicians, who made an important contribution to the cultural pulse of the city, also played the main role in the society’s concert life. As performers, conductors, and composers, they took part in more than 1,200 major Philharmonic Society concerts. Together with guest musicians, they brought the latest trends in performance and repertoire to the city: at first, they popularized the latest opera hits (fantasies, variations, and potpourri on opera melodies), and in the second half of the nineteenth century they brought the latest soloistic, chamber, and symphonic repertoire and contributed to the development of music in Slovenia.

During the early years of the Philharmonic Society, the concerts were enriched mainly by Joseph Benesch and Gašpar Mašek from Bohemia. From the second half of the nineteenth century, Anton Nedved, Hans Gerstner from Prague, and Josef Zöhrer from Vienna dominated the society’s concert life. Nedved was the most performed local composer in Ljubljana. More than fifty of his compositions were performed in at least 150 concerts in Ljubljana. Zöhrer participated in more than 350 society concerts (160 as a performer and more than 190 as a conductor), and Gerstner played in more than six hundred concerts as a concertmaster, and more than two hundred as a soloist and chamber musician.

Concerts organized by the Philharmonic Society per decade

Employment of Immigrant Musicians

PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY

Josef JELLEMIZKY

Georg EIßLER

Josef JELLEMIZKY

Georg EIßLER

Johann Georg POMMER

Caspar MASCHEK

Johann Georg ALTENBURGER

Joseph BENESCH

Josef WAGNER

Joseph BENESCH

Caspar MASCHEK

Josefine HADERLEIN

Joseph LEITERMAYER

Fanny STEWART von

Heinrich FIBY

Anton NEDVĚD

Alfred KHOM

Karl ZAPPE

Karl FRÜHLING

Carl Robert HORNICKEL

Josef ZÖHRER

Gustav MORAVEC

Hans GERSTNER

Clementina EBERHART

Georg STIARAL

Josef SKLENÁŘ

Anna LÜBECK

Carl LASNER

James Frederik LEGRAND

Luka THEODOR

Ferdinand SEIDL

Johanna Edle von POLACK

Adalbert SYRINEK

Antonie Seifhardt NEBENFÜHRER

Karl BITSCH

Franz CZAVOJÁCS

Hans PICK

Josef KASPÁREK

Franz LÖHRL

Alfred JAGSCHITZ

Friedrich RUPPRECHT

Rudolf PAULUS

Anton Theodor CHRISTOPH

Alois KERN

Josef HÖLLRIGL

Robert HÜTTL

Julius VARGA

Leopold Ferdinand ZEININGER

Karl Paul SEIFERT

Franzi von FORMACHER

Contribution of

MILITARY BANDS

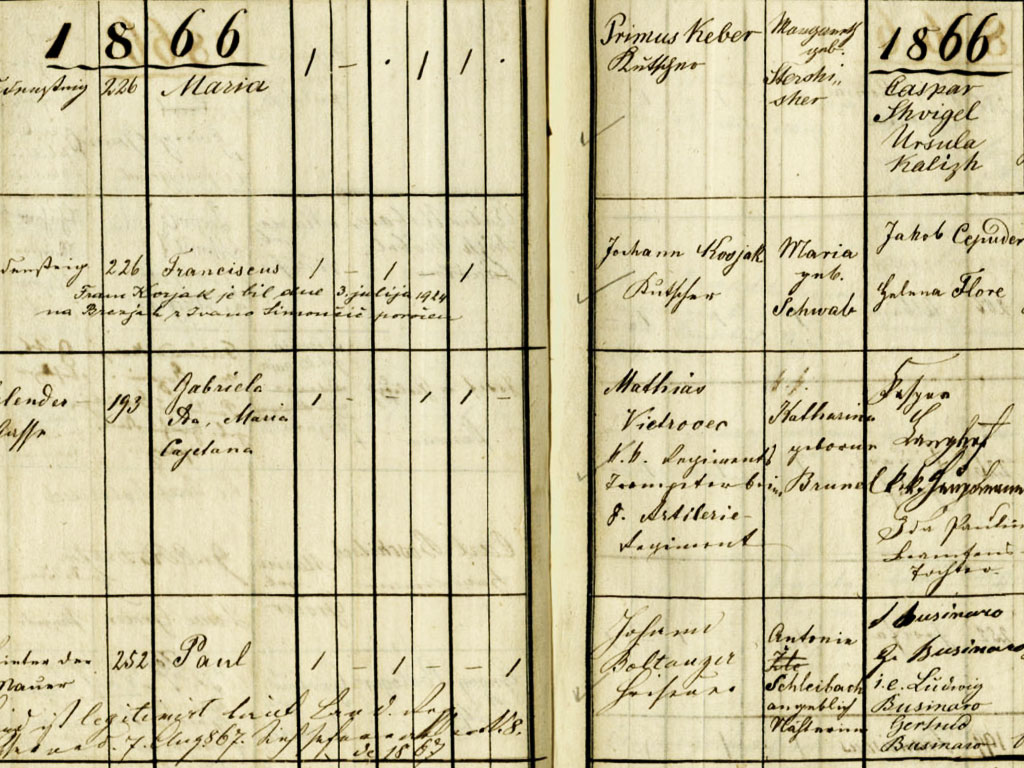

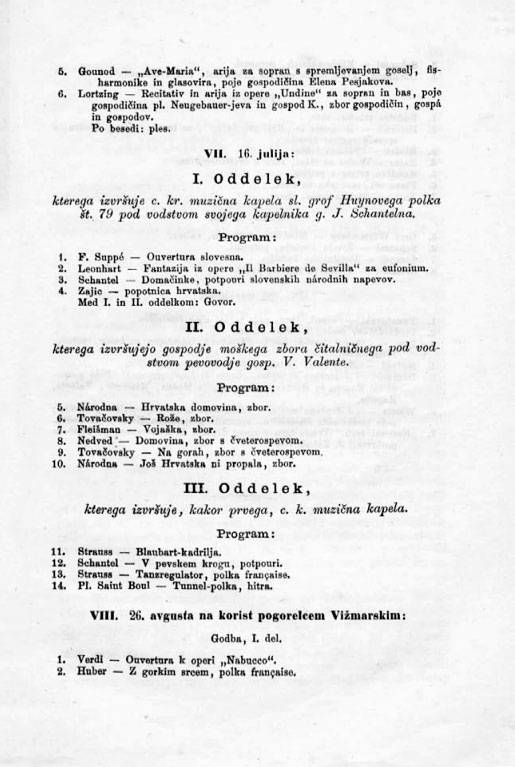

In the nineteenth century, there was no municipal symphony orchestra in Ljubljana to perform at concerts or opera performances. In order to offer regular symphonic concerts, the Philharmonic Society was obliged to join forces with military bands that were stationed in or visited the city. They cooperated not only with the Philharmonic Society, but also with theaters, the Ljubljana Reading Society and, towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the Slovenian Music Society in Ljubljana. Besides marches and waltzes, the military bands also played more challenging works from the symphonic and operatic literature. The bandmasters were mostly from Bohemia, but many other musicians from the various realms of the monarchy played in the bands or passed through the city. One of these was the military trumpeter (k. k. Regiment Trompeter beim 8 Artilerie Regiment) Mathias Wietrowetz from Bohemia, whose daughter, the famous violinist Gabrielle Wietrowetz (1866–1937), was born in Ljubljana for this reason. Among the most active military bands in Ljubljana was the military band of the 17th Infantry Regiment or Carniolan Regiment, which played in Ljubljana throughout the nineteenth century. Its most important bandmasters included Carl Handschuh, Paul Micheli, Johann Nemrawa from Bohemia, and Anton Wolf from Austria. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the 46th Regiment with Johann Schinzl from Bohemia and 79th Regiment with Georg Schantl from Graz participated in the concerts in Ljubljana. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Styrian Graz 27th Military Band flourished, especially under the baton of Theodor Anton Christoph from Odesa, and enriched the Philharmonic Society concerts in Ljubljana. Military bands participated in more than 130 concerts in Ljubljana up to the end of the First World War.

The Prelude

READING SOCIETIES

The national parliamentary elections of 1861 did not bring a more tolerant policy toward national pluralism. The situation was aggravated by conflicts between the Slovenian and German sides, with the Germans describing Slovenians as politically immature and culturally underdeveloped. Against this background, nationally conscious Slovenian enthusiasts again took up the United Slovenia (Zedinjena Slovenija) program and developed reading societies as a form of strengthening national consciousness and the cultural-political situation in the monarchy. Slovenian reading societies were inspired by the Pan-Slavic–oriented societies in Vienna and Graz, where singing played a central role. The first reading societies in Trieste, Maribor, and Ljubljana, founded in 1861, inspired the formation of new societies in large and small cities and spread the national program through their sociopolitical involvement in the countryside. Reading societies generally focused on choral singing and plays written in Slovenian. The most widespread ensembles were men’s quartets and smaller or larger choirs, but from the 1870s mixed and women’s choirs also appeared. In 1884, the Slovenian Choral Society (Slovensko pevsko društvo) was founded. It included choral societies and individual choirs from many towns and villages. The joint choirs performed at least once a year and were occasionally accompanied by military or civilian bands. Foreign musicians, especially Czechs, played a key role in the musical activities of the National Reading Society in Ljubljana, whereas the other Slovenian reading societies involved mainly local music lovers.

Establishment

NATIONAL READING SOCIETY

The National Reading Society in Ljubljana was founded in the fall of 1861 on the initiative of Janez Bleiweis and at the urging of Croatian patriots and members of the Reading Society. An important factor for its establishment was the national discord in the German-Slovenian choral society (Liedertafel), which was becoming increasingly German. The National Reading Society in Ljubljana established an extensive program, including obligatory choral singing, which in the first year was directed by Anton Nedved, a Czech and the choirmaster of the Philharmonic Society of Ljubljana. His successful work and refreshed repertoire, to which he himself contributed as a composer, led to an exodus of singers from the Philharmonic Society to the Reading Society. Nedved was forced to choose between the two sides; for financial reasons he remained loyal to the Philharmonic Society, but also continued to work with the Slovenian societies until his death.

Choirmasters

NATIONAL READING SOCIETY

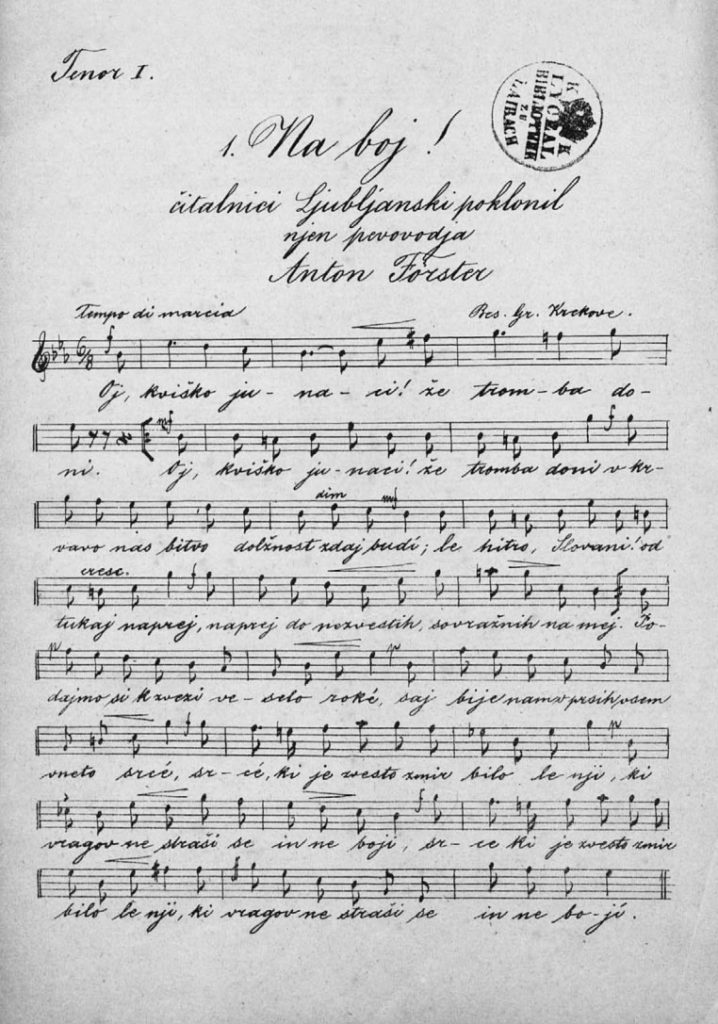

After Nedved, other musicians led the choir and continued his work. Josef Fabian from the Prague Conservatory took over the choir in 1863. In order to raise the level of the choir, he founded a singing school, transformed the all-male ensemble into a mixed choir, and performed compositionally more demanding works by Slovenian and Croatian composers. In 1867 the choir was taken over by another Czech, Anton Foerster, who introduced a singing school and wrote a manual for this purpose, a “Short Instruction for Singing Lessons” (Kratek navod za pouk v petji; 1867). In 1870 he left the choir and devoted himself to the Drama Society and the Ljubljana Cathedral Choir. Anton Stoeckl from Ljubljana was responsible for the continuation of the musical activities of the Reading Society until 1877. He added music theory to the singing school and excerpts from well-known operas to the repertoire, which the choir performed together with soloists and instrumental accompaniment.

Concert Performances

NATIONAL READING SOCIETY

Between 1867 and 1891, the National Reading Society of Ljubljana gave more than one hundred recitals (bésede), often featuring the compositions of Czech composers Anton Nedved and Anton Foerster. The concerts were also joined by various military bands led by immigrant bandmasters such as Georg Schantl, Johann Schinzl, Johann Nemrawa, Georg Mayer, Georg Stiaral, and Franz Czansky. In 1889, the Prague violinist Vitězslav Roman Moser founded a string quartet and, together with Julius Januschovsky, played several virtuoso violin pieces at the Reading Society recitals. Occasionally violinists, Music Society teachers, and members of the theater orchestras also performed at the concerts.

Prelude

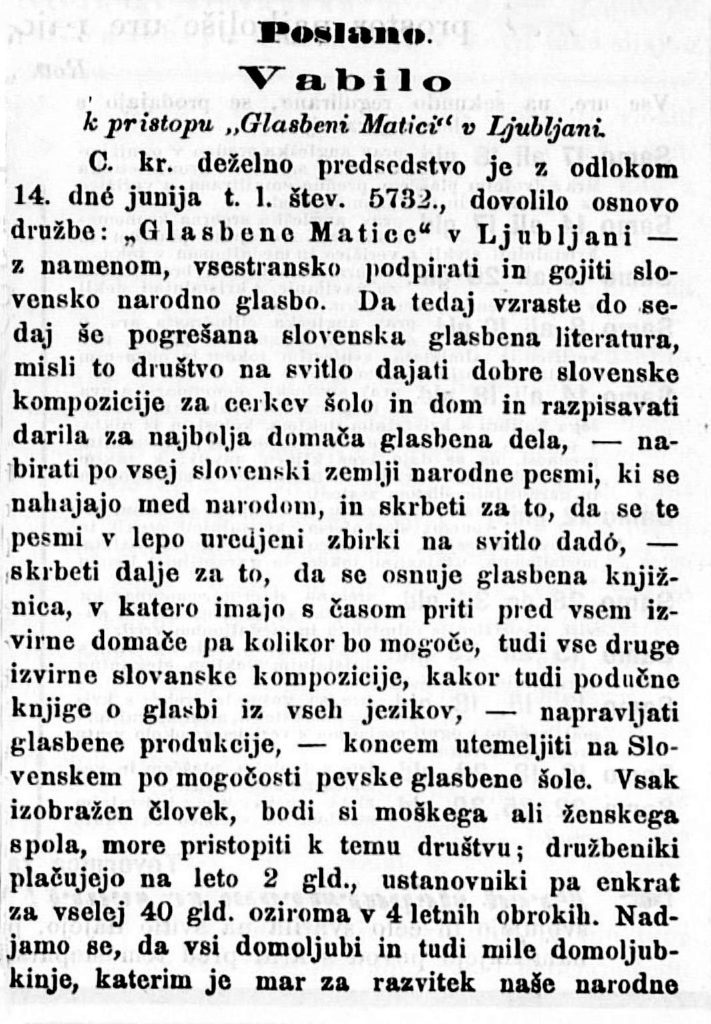

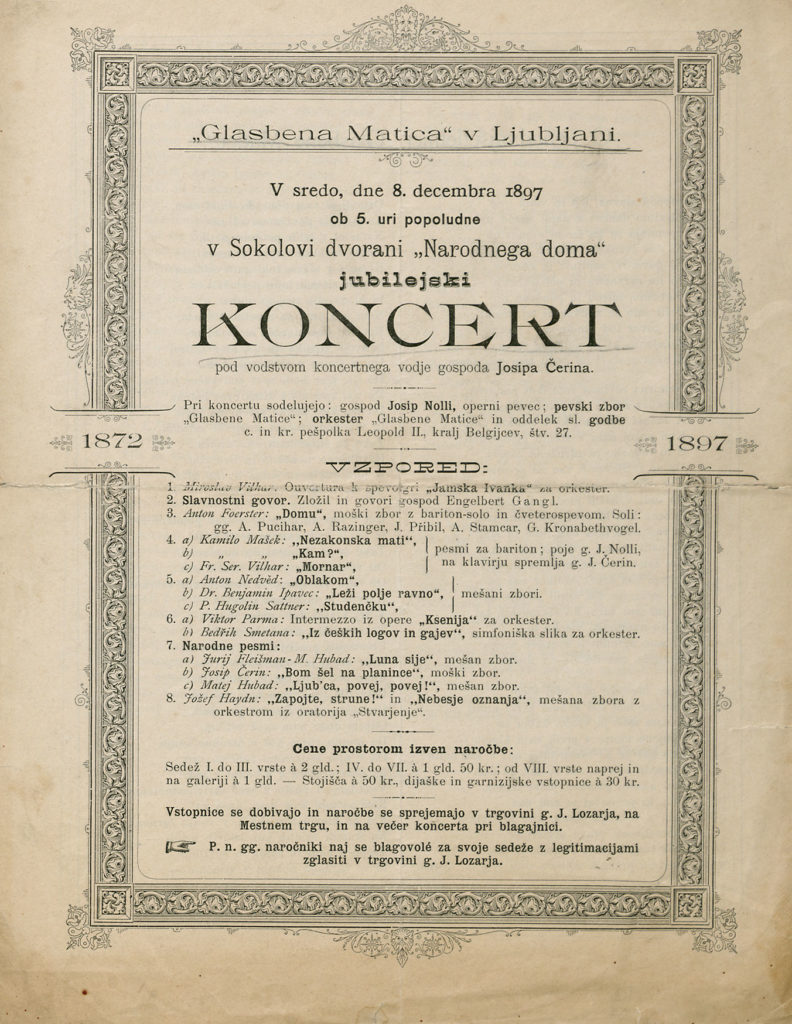

GLASBENA MATICA

From its foundation in 1872 until the end of the First World War, the Slovenian Music Society (Glasbena matica) in Ljubljana was not only a musical center, but also a cultural and national one. It brought together amateur and professional musicians, the Slovenian educated elite, politicians, and cultural figures. Its activities were strongly influenced by the tendencies of cultural nationalism with which Slovenians in the Austrian Empire tried to assert their right to a political existence as a nation, whereas on the other hand, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the idea of a national culture based on the Slovenian language and Slovenian folk music took hold. The concepts of Slavic commonality and common characteristics of Slavic nations came into focus, which was also reflected in the relationship of Slovenian and Slavic music to German music. Slavic reciprocity ran like a thread through Slovenian musical culture, and cooperation with Croatian and Czech music societies provided a better starting point for the realization of the ambitious tasks the society had set itself. Until the end of the First World War, the Music Society promoted the autonomy of Slovenian musical culture within the multiethnic Austrian Empire by publishing Slovenian works by Croatian, Czech, Serbian, and Russian composers, admitting only children of Slovenian parents to the music school, employing teachers of Slavic origin, engaging Slavic artists for concerts, and collecting manuscripts and prints by Slovenian composers in the music archive. Discover more

Establishment

GLASBENA MATICA

The idea and initiative to establish the Music Society came from enthusiastic patriots Blaž Kuhar and Vojteh Valenta. However, the application to establish the society was formally submitted by the music director of the Philharmonic Society, Anton Nedved from Bohemia, and the members of the founding committee. The initial impetus for the Music Society activities came from professional musicians, the Czechs Anton Nedved and Anton Foerster and, from 1886, especially from the Slovenian Fran Gerbič, who worked to promote professionalism in music and overcome dilettantism until the end of his life. From 1891 Matej Hubad directed the society with his initiative and diligence, becoming the active leader and driving force of the society for decades.

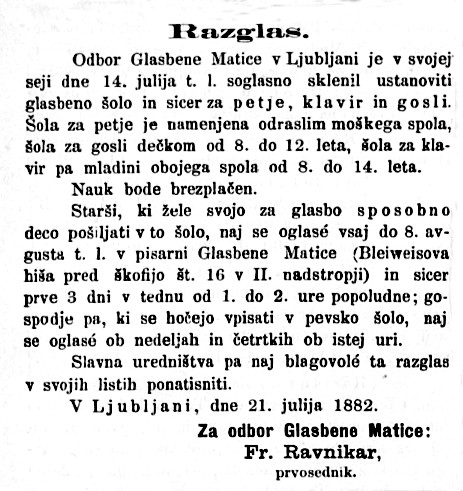

Music School

GLASBENA MATICA

The Music Society’s (Glasbena matica) main task was to establish a music school where lessons would be taught in Slovenian. In addition to this national goal, the reason for founding the music school was also the desire to provide amateur and especially professional musicians with an adequate music education, which is why the music conservatory founding was already discussed in the first committee meeting. The school started operations in 1882 and developed especially from 1886 under the leadership of Fran Gerbič. He made efforts to hire well-trained teachers, improve the curriculum, and create original textbooks. In the third year, piano, all string instruments, solo singing, choral singing (youth and men’s choir), and theory were taught; in the fifth year, orchestra rehearsals for amateurs were on the curriculum, and in the sixth year, wind and brass instruments were taught. Gerbič sought out well-trained teachers primarily at the Prague Conservatory, where he himself had studied in the 1860s. By the end of the First World War, more than twenty-five music teachers from abroad, mostly violinists, worked at the Music Society school. Most of them had studied at the Prague Conservatory, only a few in Vienna, and one in Lviv.

Music Teachers from abroad

GLASBENA MATICA

Julius Ohm JANUSCHOVSKY

Georg STIARAL

Josef WIEDEMANN

Jan Jiří DROBEČEK

Anton KUČERA

Ferdinand RIEDIGER

Gustav WAGNER

Vitězslav MOSER

Karl Hoffmeister

Jan Josef BAUDIS

Karel JERAJ

Josef VEDRAL

Julius JUNEK

Josef PROCHÁZKA

Jan Kraus

Otokar ZUSKA

Jaroslav HEYDA

Karl TARTER

Franz TAMHINA

Jan REZEK

Emanuel MAŠEK

EDVARD BÍLEK

Václav RUNKAS

Jaroslava CHLUMECKÁ

Stanislava HAJEK

Musicians’ Origins

GLASBENA MATICA

By the end of the First World War, more than twenty-five music teachers from abroad, mostly violinists, worked at the Music Society music school. Most of them had studied at the Prague Conservatory, only a few in Vienna, and one in Lviv. Thus, most of the musicians had been born in different towns in Czech territory. Some of them had been born of Czech parents outside of Czech territory in cities like Linz, Vienna, and Stavropol. The situation was similar at the Music Society branches in Novo Mesto, Gorizia, Celje, Kranj, and Trieste, where the musicians were also mostly from Bohemia and Moravia.

Origin of musicians employed at the Glasbena matica

Concert Life

GLASBENA MATICA

It was not until 1888 that the Music Society gave its first major concert with soloists, choir, and orchestra, in which Czech musicians also participated. In 1891, a choir was established as an independent part of the society; it became a permanent performing group. The concerts given by the Slovenian Music Society before the First World War were less varied and less numerous in terms of repertoire than those of the Philharmonic Society. On average, the Music Society held two society concerts per concert season with a vocal repertoire and a vocal-instrumental repertoire with both men’s and women’s choirs. In addition to concerts with a mixed program and a predominantly vocal or vocal-instrumental repertoire, the Music Society also held musical evenings with a smaller number of performers and predominantly instrumental performances, as well as social singing evenings. Between 1888 and 1918 it gave three hundred concerts in which musicians from abroad, mainly Czechs, participated as soloists, conductors, and composers in over two hundred.

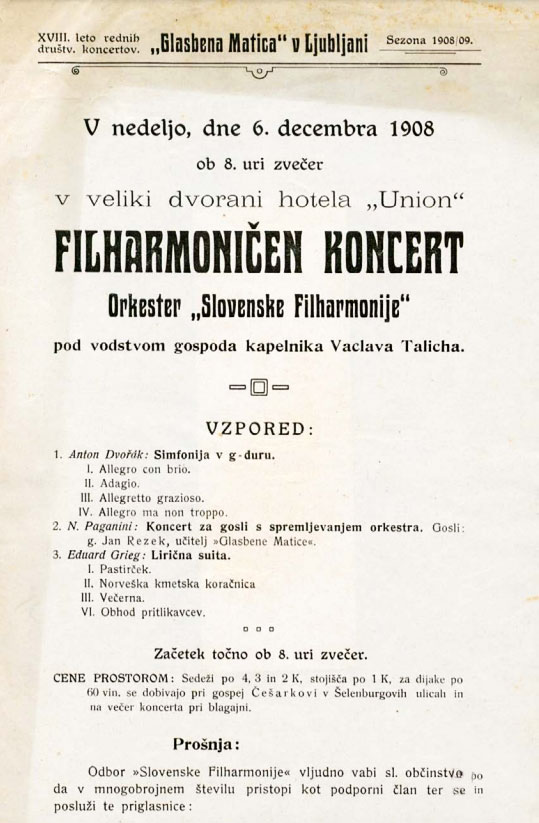

The First Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra

GLASBENA MATICA

The Music Society was aware of the problem that there was no civic orchestra in Ljubljana that could perform at concerts and opera performances. Like the Philharmonic Society, the Music Society had to hire a military band for its concerts, which the committee felt was no longer financially or politically appropriate. The Music Society therefore promoted the creation of a civilian concert and opera orchestra, the first Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra, which was active between 1908 and 1913. The first conductor was the young Prague violinist Václav Talich, the concertmaster was Jaromir Markucci from Litomyšl, and most of the orchestra members were Czechs. For this reason, the orchestra was nicknamed the “Second Czech Philharmonic.” When Talich left Ljubljana in 1912, the orchestra was taken over by another Prague violinist and military bandmaster Petr Teplý and another Czech, opera conductor Cyril Metoděj Hrazdira. During its existence, the orchestra performed only twenty-seven times at Music Society concerts, but its performances were of great importance for the promotion of Slovenian orchestral music.

Establishing Branches

GLASBENA MATICA

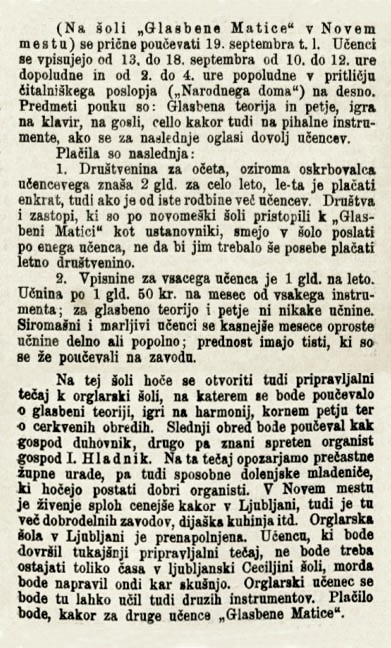

The establishment of singing and music schools throughout the entirety of Slovenian territory was one of the tasks that the board of Music Society (Glasbena matica) had already written down in its first rules. This task was put into practice more than a quarter of a century later and more than ten years after the Music Society was founded. The first branch was founded in Novo Mesto in 1898, the next in Gorizia in 1900, and branches were opened in Celje, Kranj, and Trieste in 1909. The parents of the students attending the branch school had to be members of the Slovenian Music Society. The content and form of the work of the branch schools was based on the model of the main school, and the lessons were taught according to the uniform curricula of the Slovenian Music Society. Before the First World War, the Slovenian Music Society branch schools in Novo Mesto, Gorizia, Celje, Kranj, and Trieste strengthened the cultural self-confidence of Slovenians beyond Ljubljana, the main Slovenian cultural center. The music school was at the center of their work, and by giving concerts, the branches enriched the musical life of Slovenians in Styria, the Littoral, and Upper Carniola, helping to shape the concert audience. Musical life was also shaped by musicians from Bohemia at Music Society branches throughout Slovenia.

Branch in Novo mesto

GLASBENA MATICA

The Slovenian Music Society (Glasbena matica) first tried to arouse interest in classical music by giving concerts in various Slovenian cities. In the 1897/98 season, the Lower Carniola Singing Society and the Slovenian Music Society held musical evenings in Ljubljana and Novo Mesto with performances by local singers and the Prague music teachers of Ljubljana: Karel Hoffmeister, Julij Junek, and Josef Vedral. In April 1898, the Novo Mesto branch of the Music Society was founded. The teachers were mostly Slovenians, but the violin was taught by Josip Poula from Bohemia. From 1894 he was bandmaster of the municipal brass band of Novo Mesto, later he was also a private music teacher and performed in a piano trio (consisting of Poula, Hladnik, and Dolenc). After leaving Novo Mesto for Vienna, he was succeeded by another Czech, Anton Spaček, who was “a retired master violinist and military bandmaster.” The school closed its doors in 1904 when Ignacij Hladnik opened a private music school, where the Prague violinist Rudolf Hachla, who had been concertmaster in Klagenfurt until his arrival in Novo Mesto, taught violin.

Branch in Gorizia

GLASBENA MATICA

In Gorizia, the nationally conscious Slovenian Henrik Tuma initiated the founding of a Slovenian choir and music school modeled on Ljubljana’s Slovenian Music Society. Initially a men’s choir was established, but two years later a women’s choir was added and the Prague musician Josef Michl, a student of Antonín Dvořák, became the choir director. In addition to the choir, the association also maintained a school, which by the end of 1905 already had sixty students. In addition to Michl, Emil Komel and the Czech Lovrenc Kubišta also served as teachers. After studying violin in Prague with Antonín Bennewitz, Kubišta worked in Zagreb and then in Postojna. In Gorizia he taught violin, piano, and choral singing. The Gorizia Society enriched the local musical life with its concert activities, and the concerts were attended by both Slovenians and Italians. Works by Michl were performed at the concerts, including Na Golgati (On Calvary), Pred prvimi verzi (Before the First Verses), Sokratova smrt (Death of Socrates), and Atila in ribič (Attila and the Fisherman). Concerts by foreign (mostly Czech) artists were also given. Michl also founded a string quartet and a quintet (Ivan Karlo Sancin, Silvan Pečenko, Ciril Eržen, Josip Michl, and August Pertot), which performed publicly several times in Gorizia.

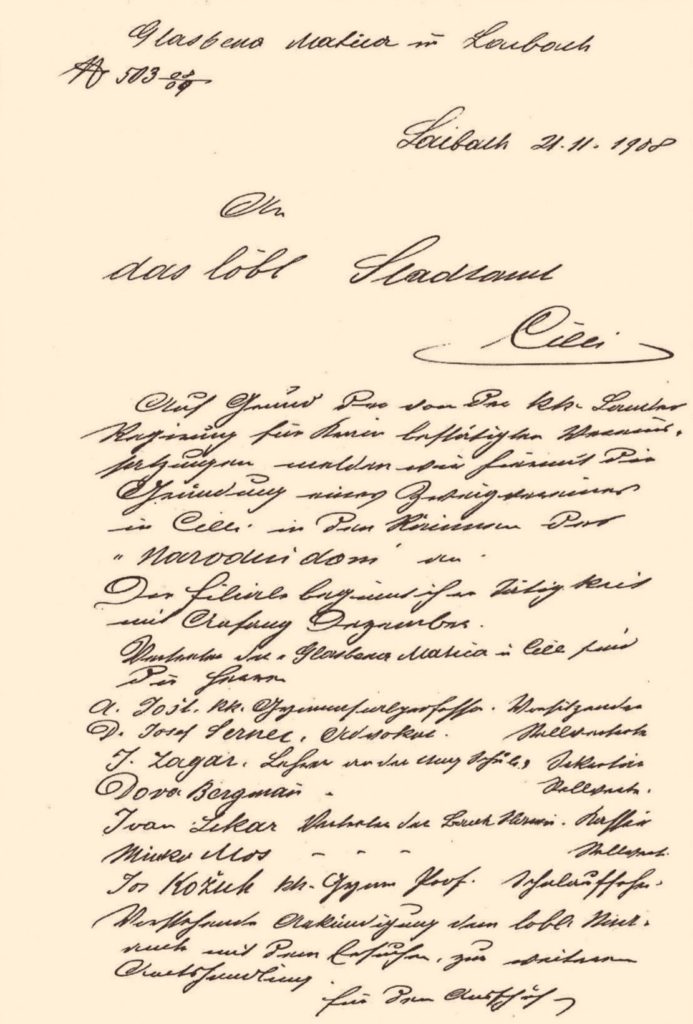

Branch in Celje

GLASBENA MATICA

This Music Society branch started its activities in Celje at the end of 1908, but was officially approved only in October 1909. The first director was Adolf Feix from Bohemia, who was succeeded in 1910 by the Prague violinist Wilhelm Seifert. Seifert died in 1912 and was succeeded by another Czech, Václav Engerer. With the outbreak of the First World War, musical development declined sharply, mainly due to the absence of many young musicians who had been mobilized and the lack of an underclass that could be trained in this situation. After the end of the war, the music situation also changed radically, because many important musicians who had once played significant roles in Celje musical life departed. After the war, one of the last musicians from Bohemia, Lovrenc Kubišta, taught at the school and led the city’s brass band. The 1920s were marked by the arrival of the Sancin brothers and the beginning of the dominance of local musicians in Celje.

Branch in Kranj

GLASBENA MATICA

The initiative to establish a music school in Kranj came from the choir of the Reading Society in Kranj. The Kranj branch of the Music Society was founded at the end of 1909. The new school worked according to the curriculum of the Slovenian Music Society, which supervised its work and appointed the teachers. The first violin teacher was the Czech Václav Doršner, who was succeeded the following year by the Prague violinist Zíkmund Polášek. After studying at the Prague Conservatory with the famous violin teacher Otakar Ševčík, he was concertmaster in Kraków and a member of orchestras in Lviv, Warsaw, and Prague. He came to Kranj from Klagenfurt. It is thanks to him that between 1910 and 1912 the school had twice as many violin pupils as piano students. Together with another Prague violinist, Josef Vedral, Polášek arranged Slovenian folk songs for violin lessons, and his Lullaby for Violin and Piano was published in Novi akordi (New Chords).

Branch in Trieste

GLASBENA MATICA

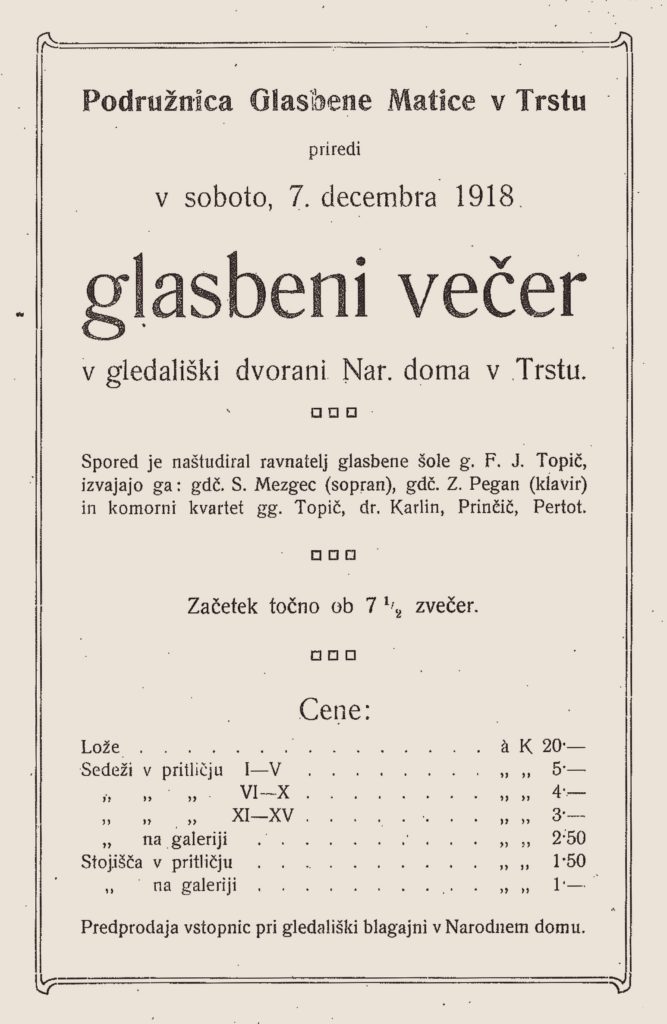

In the fall of 1909, the teacher Karel Mahkota initiated the foundation of a music school in Trieste, which he directed for the first two years. Initially, Emil Adamič taught piano and Makhota taught violin and piano; later solo singing and other instruments were also taught, so that an independent orchestra could be built. When Viktor Šonc, who had studied composition in Prague, took over the school, it began to develop. He taught piano, theory, solo singing, youth choir, and string orchestra. In addition to his teaching, he also collected and arranged folk songs and composed. Before the war, the Prague violinist and retired military bandmaster Petr Teplý, who worked in Trieste between 1902 and 1912, began teaching the violin according to Ševčík’s method. In 1914/15 the school rented premises in the National Hall, but during the war the school did not function well. After the war, music was taught by another Prague violinist Fran Topič (piano, violin, soloists), Avgust Ivančič (violin) and Vasilij Mirk (piano, theory, and harmony). Concert activity developed in Trieste from the foundation of the National Hall in 1904, and later also due to the music school.

Trieste

NATIONAL HALL | NARODNI DOM

Due to its numerous trade relations, Trieste was home to people of many ethnicities at the turn of the century. Italians, Germans, and Slovenians were the most numerous inhabitants of the city. At the beginning of the twentieth century, about sixty thousand Slovenians lived in Trieste, and the surrounding area was entirely Slovenian. The city’s main professional music institution was the opera house, and Trieste’s theaters were also important venues for concerts. Beginning in the late 1870s, Slovenian music societies increasingly appeared in Trieste and the surrounding area, especially choirs, brass bands, and tamburitza orchestras. In the period before the First World War, Slovenian cultural activities in Trieste reached their peak with the opening of the National Hall in 1904, which sparked further development primarily among Slovenian cultural associations. Based on the Edinost newspaper and the preserved concert programs, more than three hundred concerts that took place in the National Hall between 1904 and 1920 have been reconstructed. Numerous Slovenian societies and guest musicians, mainly Czechs, performed at the National Hall. The military band of the 97th Infantry Regiment and the military band of the 4th Bosnian Infantry Regiment were at the center of Slovenian concert life at the National Hall in Trieste. Among the foreign musicians, the Czechs Petr Teplý and Fran Topič, as well as the occasional music director Franz Zita, contributed to Slovenian concert life in Trieste. All three were active in Maribor after the war. Almost all Slovenian associations in Trieste also performed compositions by Czech musicians from Ljubljana. Anton Foerster and Anton Nedved were the most prominent, and to a lesser extent Josef Michl, Josef Procházka, and Anton Jakl.